EU Pulls Back on Sustainability: Our Perspective

As the political debate intensifies over the future of the EU’s sustainability framework, particularly the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), and now the Green Claims Directive (GCD), much of the discussion has focused on whether these regulations impose excessive burdens on companies or risk undermining European competitiveness.

While we understand the concerns driving these conversations, we believe the discussion risks becoming too narrowly framed around compliance costs, without fully acknowledging how sustainability reporting requirements shape capital markets, investor decisions, and financial risk management more broadly.

Current Market Trends

1. Investors want companies with strong sustainable practices and strategies

Current financial market dynamics reflect a real investor demand for resilient, ESG-integrated portfolios. In parallel, consumer behaviour continues to favour greener options, especially in B2C markets.These trends will persist, with or without a regulation that supports them.

If the EU does not provide a clear and credible framework, private labelling systems or external standards will inevitably fill the gap, increasing compliance costs for companies trying to maintain a competitive edge, but without the public supervision or comparability that official EU frameworks ensure.

Recent data from the Netherlands Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM), as presented in its Rapportage Financiële Stabiliteit (2024), illustrate these dynamics well. While the market for green bonds continues to grow, the demand for Article 9 SFDR funds appears to decrease, suggesting a weakening appetite for investment strategies with sustainability as a primary objective.

.png)

At the same time, the interest in transition-oriented products, particularly those classified under Article 8, is increasing. These instruments are often designed to support corporate transition plans, offering a more flexible and accessible route to sustainable investment.

This shift further reinforces the need for a regulatory framework that can accommodate a broader diversity of sustainability strategies, from high-impact funds to those enabling progressive transition.

2. Companies are suffering losses due to the legal uncertainty created by the Omnibus Proposal

Prior to the Omnibus, we observed a period of growing sustainability ambition across the market. Many companies, particularly front-runners in innovation and risk-aware industries were making bold investments: developing new business models, piloting transitional solutions, turning sustainability into a competitive differentiator, or simply striving to meet the regulatory minimums while improving internal resilience.

The announcement of delays and potential deregulation of CSRD requirements has significantly disrupted this trajectory. Several companies have seen their investments partially or wholly sunk. Others, particularly those who were hesitant from the outset, have interpreted the delay as a reason not to act at all, postponing the creation of reliable data systems or risk-mapping processes, despite the fact that climate-related financial risks continue to mount.

From an investor’s perspective, it was widely expected that companies with approximately 250–1,000 employees would begin reporting CSRD-aligned data by mid-2026. That timeline is now postponed. In the absence of clear requirements, many market participants face a choice: either to collect the data independently (e.g. via SFDR’s Principal Adverse Impact indicators), or to accept the data gaps that limit the ESG assessment.

In practice, we increasingly see a kind of ‘CSRD light’ approach emerging: firms follow the logic of the CSRD, but implement only the most relevant aspects to their financials, skipping what is not seen as applicable. Nevertheless, cost–benefit considerations often lead to more cautious strategies, and there are signs that some ESG projects may face significant cuts.

With ongoing geopolitical uncertainty and pressure on import/export-facing businesses, many market actors now appear to be adopting await-and-see approach, holding off their investments until regulatory clarity is restored.

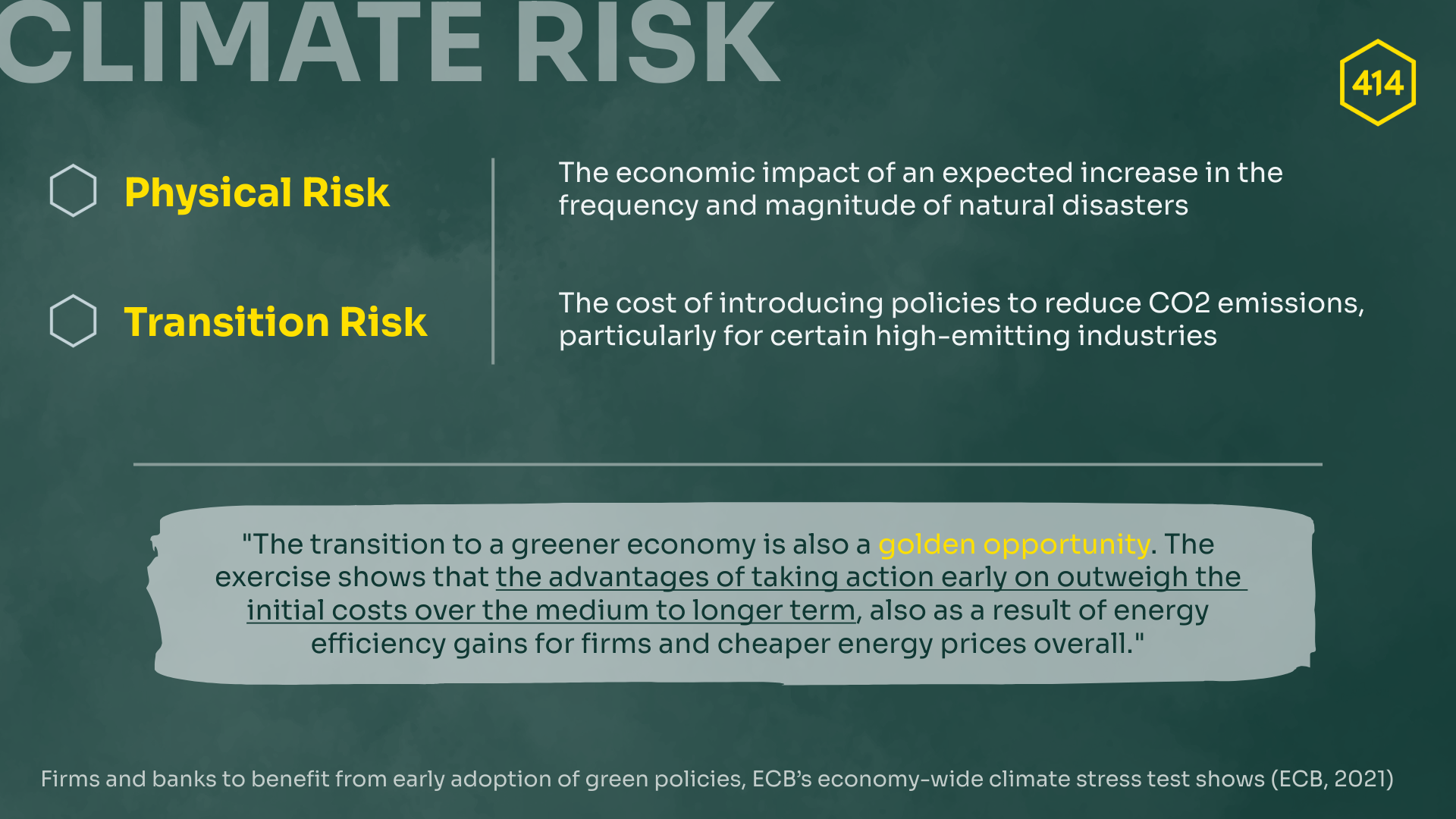

Climate Risk, Financial Stability, and the Need for Reliable Sustainability Data

This retaliation seems not only shortsighted but ultimately dangerous. The underlying risks keep accumulating and, sooner or later, climate change will return as the central concern on policy, investor, and consumer agendas. At that point, companies without established data infrastructures, decarbonisation strategies, or credible transition plans will face overwhelming exposure, with few tools left to adapt.

Moreover, investments in high-emission sectors are increasingly mispriced. As soon as viable low-carbon alternatives emerge and are scaled by market or regulatory mechanisms, the value of assets in highly polluting business models could collapse rapidly, erasing their value and destabilising portfolios.

Conversely, those who have invested early in credible, science-based sustainability strategies stand to benefit from long-term profitability and reduced risk, shows a test conducted by the European Central Bank (ECB).

Nevertheless, even front-runners will suffer the consequences of the general scarcity of ESG data. In its latest opinion, the ECB strongly warns that sustainability information is critical for the financial sector to understand and price sustainability-related risks, and that the absence of reliable ESG data may obscure significant climate-related financial exposures, thereby threatening financial stability.

Voluntary reporting also leads to lower data quality

Some of the risks that the ECB found when companies report without the regulatory pressure are:

- Self-selection bias: Only the better performing companies disclose, which makes it impossible to derive an accurate benchmark.

- Greenwashing risks: The lack of verification and legal guidance can lead to misleading claims, even unintentionally.

- Legal uncertainty and low data comparability.

- Greater reliance on proxies, which could distort risk assessments.

The shift we are witnessing puts at risk the whole European economy

It is not only about ensuring environmental protection, it is about protecting Europe’s financial system, industrial base, and innovation capacity. Extreme weather events such as floodings can have direct macroeconomic consequences, but they also pose indirect risks to financial institutions, including banks, insurers, pension funds, and investment firms. Delays in the sustainability transition only increase the likelihood and potential impact of these risks materialising.

.png)

The urgency is underscored by current climate projections. According to the United Nations, the world is on track for a global temperature rise of 2.6 to 3.1°C under existing policies, far above the 1.5°C target set under the Paris Agreement.

Without additional, concrete action, that goal is out of reach and the risk landscape facing both companies and financial institutions will continue to deteriorate.

Transparency and comparability of sustainability data are therefore essential, not just to maintain investor trust, but to ensure that financial markets can continue to finance the green transition in a risk-informed and forward-looking way.

What we expect from the EU

The European project has always been grounded in the idea that cooperation creates more value than competition without rules, a vision rooted in the post-war logic of mutual resilience and shared benefit.

Economic growth that disregards planetary boundaries or externalises harm to other regions may deliver short-term competitiveness, but it is ultimately unsustainable. It creates a classic tragedy of the commons, where individual incentives lead to collective loss. If we overexploit the natural and social capital on which our societies depend, there will be no long-term prosperity to protect.

The SFDR and CSRD, despite their flaws, are tools that help market actors internalise those shared responsibilities and navigate risks and opportunities more thoughtfully.

In a geopolitical moment when others turn inward or seek to weaken standards, the EU remains well placed to lead by example. The sustainability reporting and due diligence frameworks are an opportunity to reinforce Europe’s global edge in sustainable finance, and to make our economic model more competitive precisely because, unlike any other, it is values-driven.

For now, the SFDR and CSRD remain a transparency tool. They reflect the EU’s longstanding commitment to not just creating wealth and welfare, but to considering how that wealth is generated, ensuring it is done in a way that is fair, future-proof, and consistent with our shared values.

If, in the future, the EU wishes to go further by using legislation not just to enable investor appetite, but to shape it, then it will need to move beyond disclosure and adopt a more proactive “carrot and stick” model: rewarding investment in genuinely sustainable activities with financial advantages (such as preferential lending rates or regulatory incentives), while discouraging harmful practices through meaningful costs or constraints.

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is a good example of how to rebalance trade incentives in favour of low-carbon production.

Conclusion

The political momentum to dilute the EU’s sustainability framework risks trading short-term administrative relief for long-term structural vulnerability.

The CSRD and SFDR enable investors to manage risk, firms to future-proof their operations, and public institutions to monitor systemic exposures. Without reliable, comparable ESG data, transition finance becomes guesswork, and climate-related risks are left to build up unmitigated until they become unmanageable.

If the goal is to ensure European competitiveness, then dismantling the tools that allow markets to function with foresight and integrity is the wrong starting point. Sustainability has always been about anticipating tomorrow’s constraints and turning them into today’s opportunities.

Weakening these directives now may delay some costs, but it also delays the transition and increases the price we’ll pay when climate and social risks inevitably return to the top of the agenda.

.png)

.png)